A portion of the Stewart family story began in the Ulster region of Ireland in the 1600s.

Three centuries and many arduous journeys later, their descendants began homesteading over 2,000 acres in a narrow canyon beneath towering Mount Timpanogos, in the area now known as Sundance.

According to Stewart Olsen, his branch of the Stewarts made the voyage to Boston in 1670. Following various moves to locales in the east, Philander Barrett Stewart arrived in the Ohio Valley in 1803, joining the LDS church there. Andrew Jackson, Jr., Olsen’s great grandfather, was born in Iowa in 1846.

The family, along with many other Mormons, joined the LDS movement heading west for the wide-open spaces in the Rocky Mountains.

The family, along with many other Mormons, joined the LDS movement heading west for the wide-open spaces in the Rocky Mountains.

Andrew’s two sons, John Riggs and Scott Pease enjoyed accompanying their father on his government surveying jobs taking them throughout Utah. The senior Stewart worked as Deputy U.S. Surveyor for 40 years. His sons learned his craft and became very interested in the as yet uncharted North Fork of Provo Canyon in 1899.

“It was the beauty of the high peaks, open fields, abundant water and solitude that attracted them to this spot,” said Olsen from his house on Eleanor Lane in Sundance. Eleanor, his mother, daughter of John Riggs, was a law school graduate of the University of Utah.

The brothers quickly homesteaded 160 acres each and encouraged other family members to do the same. Th eir North Fork Investment Company eventually comprised approximately 3,500 acres and was later divided between the sons.

Olsen tells how the old five-mile logging road/sheep trail, uphill from Wildwood Resort in Provo Canyon, crossed the tumbling North Fork Creek nine times, heading to what was known as Stewart Flat (present day Sundance Village).

“In the summer, the Stewart women and children would load their buckboards with provisions and hitch up two teams of horses to get to the homesteads.” The trip from Provo, 16 plus miles, took all day. Some of the passengers had to trail the wagons, placing rocks behind the wheels on sharp inclines when the horses needed to rest.

The early houses were single-room log cabins with sod roofs, straw tick mattresses and a wood stove. Wooden and screen coolers were stashed creekside, and outhouses were utilized for many years. A milk cow and a pig were often brought along for the summer. The children and their cousins climbed trees, fished and hiked all summer; Stewart Falls and Timp Cirque were the favored routes.

John Riggs raised prize potatoes on “The Farm,” property now occupied by Robert Redford’s home. All the Stewart children were recruited at harvest time.

His daughter, Eleanor, once fell off a horse when she was six years old, broke her arm and had to go by wagon to Vivian Park, then on to Provo for medical attention via the Heber Creeper train running through Provo Canyon from Heber to Provo—a long journey for a little girl in pain.

A rough road was created in 1920, allowing some vehicles access to Stewart Flat, but steep grades often required drivers to back up the hill in reverse gear. If the cars couldn’t make it, people parked and walked to the homesteads.

Acreage in Aspen Grove on Stewart Flat, donated to BYU by the investment company, was the starting point of an immensely popular summer hike up sheep trails to Timapanogos’ summit, led by the college’s energetic and beloved athletic director, Eugene “Timp” Roberts. Beginning in 1912, his hike grew massive in size, creating a miles-long line of participants in later years.

The annual hike was a mid-July weekend extravaganza consisting of camping, robust meals, large crowds and bonfire entertainment. The Stewart children oft en joined enthusiastic hikers hoping to reach the 11,752-foot summit. Nineteen-year-old Barbara Stewart earned fi rst place in the 1955 ascent. However, too many people on the mountain over the years created problems of refuse, waste and destruction of fl ora and fauna; the 59-year annual pilgrimage ended in 1970, by joint agreement of the U.S. Forest Service, BYU representatives and community leaders.

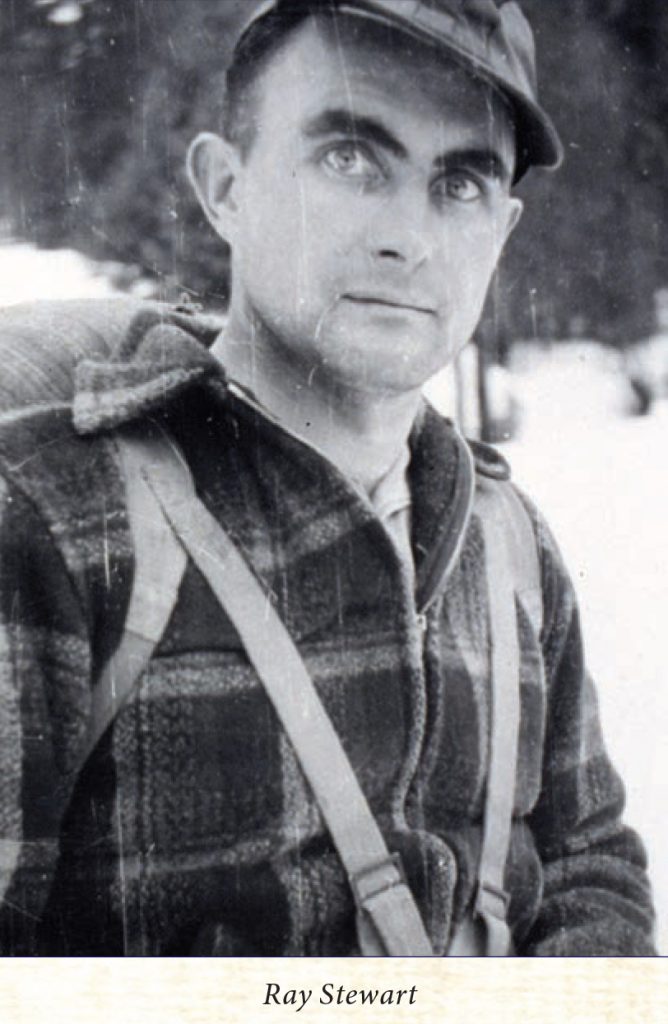

Barbara’s father Ray, Scott’s son, took an early interest in skiing, fashioning rough pine skis in his junior high school woodworking shop when he was 12. What better place to test them than on his father’s land high on the flanks of Timpanogos?

Alta was the go-to ski area in Utah’s early days. There Ray met lifelong friends who later helped him create Timp Haven, the ski area predecessor of Sundance. He worked night shifts at the Geneva Steel Plant in Provo and day shifts at his fledging ski operation.

Alta was the go-to ski area in Utah’s early days. There Ray met lifelong friends who later helped him create Timp Haven, the ski area predecessor of Sundance. He worked night shifts at the Geneva Steel Plant in Provo and day shifts at his fledging ski operation.

“Every night we had to lug the battery and gas cans from the rope tow to our cabin to prevent freezing,” Barbara remembers. “My father was always repairing, splicing and figuring out how to make things work.” A lift at present day Sundance bears Ray’s name, commemorating the man who designed the lift s, instructed and skied there until he was 81.

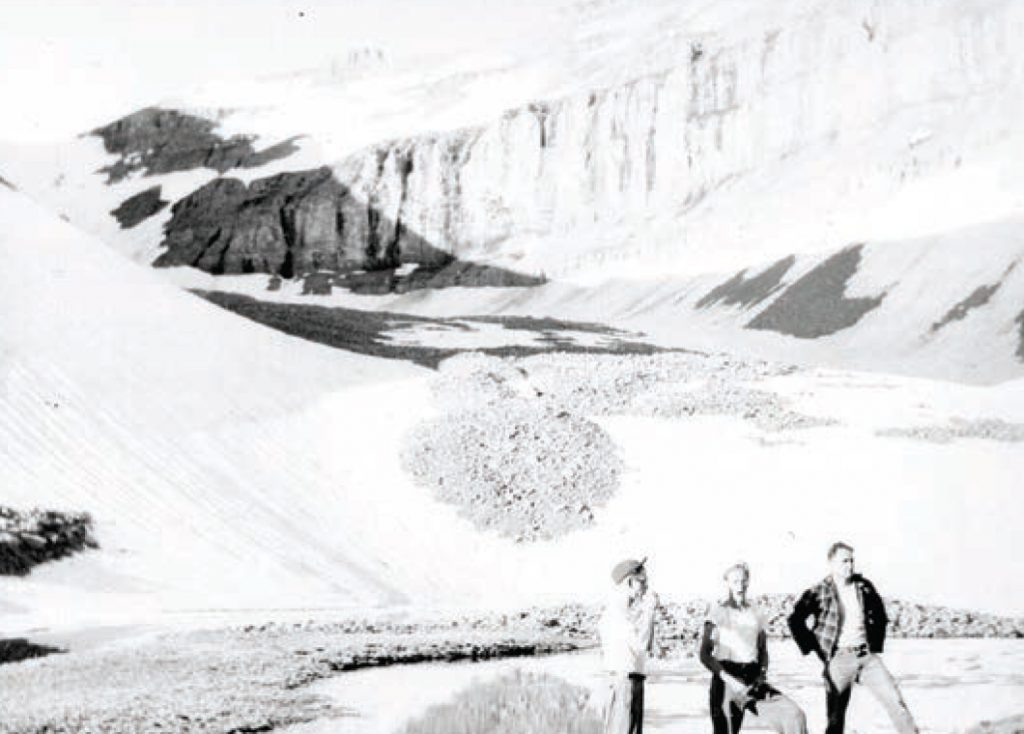

Billed in 1941 as the latest ski race on the most southerly glacier in the U.S., organizers of the Mount Timpanogos Glacier Cup Slalom Race piggybacked the famous Timpanogos Hike in July with their logistically challenging event. Skis, boots and racer necessities were hauled up to the glacier by pack horse. In those days the glacier covered more ground than today; it is now called a snowfield by some geologists. The race ended after four exciting years.

Screen star Redford fell in love with the canyon in the 1960s and succeeded in purchasing a sizable chunk of Stewart land, renaming the area Sundance. His ecologically-responsible property and ski resort complement and blend into the still jaw-dropping scen-ery in Timpanogos’ shadow.

When riding the chairlift there summer or winter, you just may meet some of the more than 100 family members of this extraordinary pioneer family.