RECONNECTING WITH PURPOSE & PLANET IN Africa’s Outback

Anyone who has ever flipped through the glossy pages of a travel magazine or Googled “African safari” has likely been inundated with images of five-star luxury lodges boasting lavish amenities—treetop massages, gourmet meals, open-air Jacuzzis on a private sundeck.

And if this type of safari experience appeals to you, the Okavango Guiding School’s Kwapa Camp is definitely not your place.

But for those seeking an authentic wilderness experience—one that will likely put hair on your chest—Kwapa Camp should be at the top of your list.

But for those seeking an authentic wilderness experience—one that will likely put hair on your chest—Kwapa Camp should be at the top of your list.

Kwapa Camp (which I can only assume is Setswana for “Everything here can kill you”), is nestled on the banks of the Kwapa River in Botswana’s Okavango Delta, the ideal setting for those whose tether to nature and nurture is tattered and in dire need of repair.

“This is not a passive experience,” admits the camp’s owner, Grant Reed. “At Okavango Guiding School, we seek to provide authentic Africa, the way it is meant to be seen, heard, and felt.”

This includes activities such as sidestepping lethal snakes on your way to fill a bucket with river water to rinse off a layer of grime. It might not sound appealing at first, but one sunset here will change your mind. And your heart. For all the right reasons, this is not the Africa typically marketed to American tourists.

“People oft en come to Africa wanting to see the big five, and most guides will just find those animals and point. But that’s a superficial experience,” Grant notes. “It’s a bit like going to New York, taking a photo the Statue of Liberty, and saying you’ve seen America. You haven’t seen anything, all you’ve done is check a box.”

“People oft en come to Africa wanting to see the big five, and most guides will just find those animals and point. But that’s a superficial experience,” Grant notes. “It’s a bit like going to New York, taking a photo the Statue of Liberty, and saying you’ve seen America. You haven’t seen anything, all you’ve done is check a box.”

Rest assured, Okavango Guiding School does not fit in any box. It’s a bit like nature’s university, offering a number of different courses to major in.

Here, people can qualify to become a professional safari guide, learn bush survival skills, or simply reconnect by way of disconnect. Th ere is no Wi-Fi, but don’t let that fool you—you will definitely experience a strong connection.

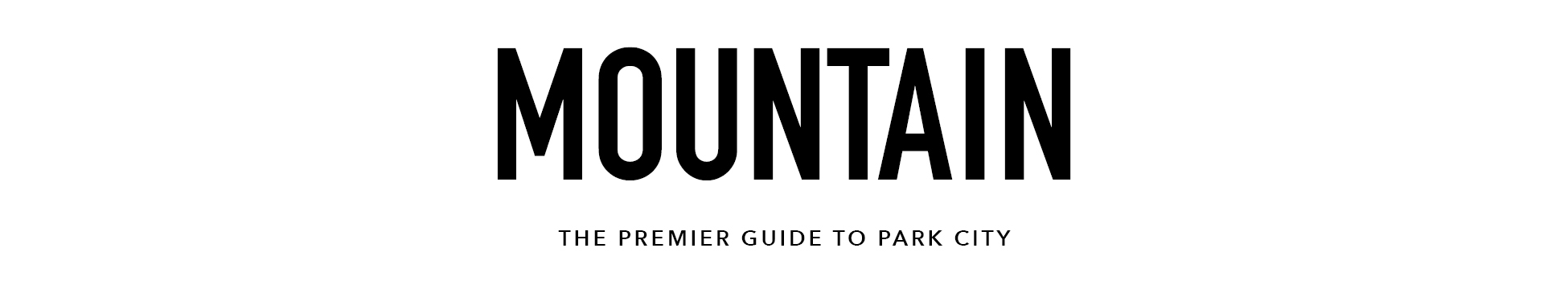

“When you gather around a track, and everyone is flipping through a tracking book and the trainer is pointing out features to help the group determine the animal’s pace, gender, age and how long ago it was in that spot—suddenly everyone is engrossed in that animal’s life,” Grant explains. “And the story doesn’t end with a sighting. If you’re trying to find an aardvark, it’s not just about the tracks. It’s about the termites too. A termite mound is a huge part of an aardvark’s story. People tend to dismiss insects, but the ecosystem collapses without them. It’s the same with plants and soil. Everything has a role.”

So how do you get a group of people who only want to see an elephant, excited about trees, leaves and bugs? Enter guides Jami Van Der Merwe and Julien Biget. They were the instructors supervising my group; a random collection of eight people spending time at Kwapa Camp for vastly different reasons—some with safari guiding hopes, others looking to deepen their understanding of the natural world, and a few working their way through a midlife crisis.

After our first day learning about bush life, an afternoon game drive was announced. “Anything special you’d like to see?” Jami asked us.

“Giraffes,” a few in the group replied.

Nodding his head in agreement, Jami hopped into the tracker’s seat on the front of the open-air Land Cruiser, Julien behind the wheel. “Let’s stop here and see if we can identify this bird,” he said a few minutes into the drive. “Everyone have a look with your binoculars.”

The eight of us exchange curious glances. We enrolled in safari school and our instructor apparently does not know the difference between a bird and a giraffe.

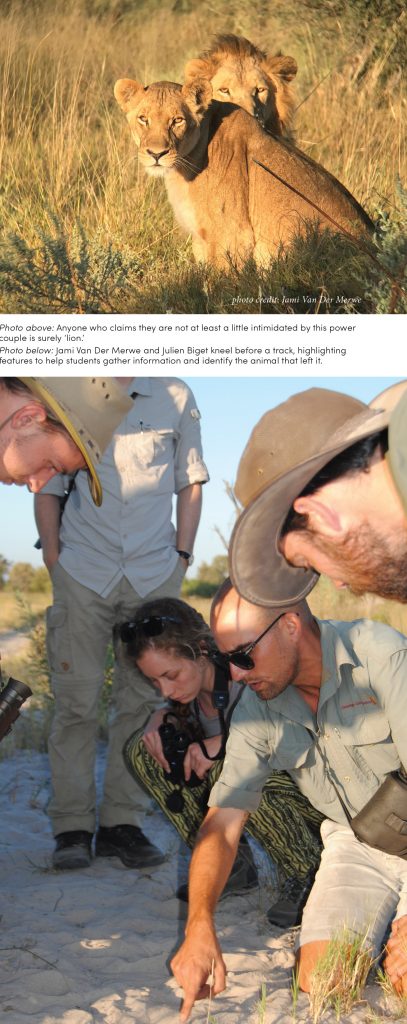

“I’ll mimic its call for you,” Jami tells us just before making a noise that seems to combine chattering his teeth, rasping for breath and whistling at the same time. Th e bird tilts its head quizzically, then fl ies to a neighboring tree. “Look at the shallow undulating flight pattern,” Jami instructs. “Notice the features: brown head and back, a lighter brown breast, red beak, orange eye with a beautiful yellow ring around it. What is it?”

Flipping through a combination of books and apps, we identify the bird as a red-billed oxpecker. “Well done,” Jami says as he hops off of the vehicle (barefoot) to gather leaves from the ground. “Look closely at all the traits,” he says as he carefully distributes his findings.

We investigate our personal sample, testing the pads of our thumbs against the thorns, wondering what exactly we are supposed to be noticing. It’s green is the only detail I can offer.

“You can easily identify this tree by its large kidney-shaped, seed-carrying pods,” Jami explains. “It has bipinnately compound leaves and paired thorns at the nodes. Notice the axillary bud at the base of the petiole and the prominent side veins,” he says pointing to each attribute. “These characteristics help clarify the species.”

The only thing this lesson clarified for me was that I have zero future as an arborist.

Jami continues on and tells us the tree’s pods can be used to treat ear infections, the bark helps with upset stomach, and its root will relieve a toothache, cough, even tuberculosis. It’s the bush version of a first-aid kit.

Great. We’re less than 24 hours into our course and our trainer is a tree whisperer. Our faces must suggest such thought.

As if reading our minds, Jami conceals a coy smile and asks, “What do you think an oxpecker eats?”

And that’s when we begin to understand—the bird and the tree must be connected to the giraffes we hope to see.

“Oxpeckers are vampire birds,” he continues. “Th ey eat ticks off their mammalian hosts. It’s a win-win relationship known as mutualistic symbiosis. And these trees here, they’re camel thorn acacias. Giraff es love eating them.”

By now, the connection signal is at full strength.

Oxpeckers + acacias = giraffe. Basic bush math.

As if they’re all in on the lesson, the red-billed oxpecker lunges from its perch and greets two timid towers as they gracefully glide into view and begin nibbling on an acacia.

Over the next few days it becomes clear Jami is the bush version of Stephen Hawking. With his laser pointer, he highlights constellations, planets and galaxies, noting how important astronomy is to wayfi nding at night for a guide. Ecology, geometry, philosophy, physiology, weather, scientific names for every living organism, photosynthesis, evolution, the reproductive traits of insects/birds/reptiles/mammals, molecular physics, quantum gravity—he can discuss them all in mind-blowing detail, and does so while gazing through his binoculars at one of the over 1,200 birds he can identify by either sight, sound, or behavior.

Throughout the course, every member of the group marvels at his off -the-cuff knowledge. Someone asks, “Do you memorize every book you read? You know everything.”

“That’s not true. I don’t know anything about Rihanna,” he replies deadpan.

A refreshing lack of pop-culture knowledge aside, Jami can be best described as the hypothetical love child of Rain Man and Indiana Jones, who was given up for adoption and raised by Gandhi.

A compassionate conservationist, he follows a vegan lifestyle and actively pursues his connection to earth. So much so that he rarely wears shoes, except for when chasing puff adders in tall grass, which he does with alarming frequency. Upon catching one that has slithered a bit too close to camp, Jami holds the snake delicately, similar to how a jeweler might present a diamond necklace to the Queen, and informs us he’s doing so to support the snake’s rib cage. “We don’t want to hurt her, just relocate her. Isn’t she gorgeous?”

It is not the word I would use to describe a highly venomous snake, but I am oddly comforted by his standard of beauty. Mostly because I haven’t seen a mirror in over a week.

As he releases the creature far from camp, it is obvious Jami is genuinely awed and appreciative of his time with it. His benevolence for all living beings is infinite. When he later shares with us a story of refugees fl eeing Zimbabwe, child-sized footprints crisscrossing the dangerous wilds of Kruger National Park in hopes of a better life, his Adam’s apple quivers with empathy.

As he releases the creature far from camp, it is obvious Jami is genuinely awed and appreciative of his time with it. His benevolence for all living beings is infinite. When he later shares with us a story of refugees fl eeing Zimbabwe, child-sized footprints crisscrossing the dangerous wilds of Kruger National Park in hopes of a better life, his Adam’s apple quivers with empathy.

“We need to get past the idea that some people don’t have value,” he says gently. “Every single soul has a purpose and potential. If you learn one thing from me, I hope it is this—people matter. You cannot call yourself a conservationist if you don’t care about your fellow man.”

Comments like this are part of Jami’s natural dialogue. Th ey are not forced or delivered sanctimoniously; they are his prayer to Mother Earth.

“It’s not an act,” fellow trainer Julien Biget confi rms. “In every moment of every day, Jami is motivated by kindness. He’s made me a better bushman and a better human.”

On looks alone, Julien resembles an outlaw cowboy slightly more than an African wilderness guide—a bit like a bearded Ben A ffl eck starring in a Roy Rogers western. You half expect to see him saunter up on a horse with the theme music from Gunsmoke playing in the background, spurs continuing to spin long after he’s stopped moving.

But his scrubland instincts are quickly proven when a strange barking noise ricochets throughout the camp. He and Jami exchange a glance, nod in wordless agreement, and collect their gear—water, binoculars, a rifl e just in case. Th e students gathered around the communal study table know something exciting is about to happen, if only because Jami is actually putting on his shoes.

Grabbing his worn leather hat—its purpose equal parts sentiment and necessity—Julien tells us, “Th at was a kudu alarm call. Let’s head that way and see what’s going on.”

During the drive, Julien explains kudu behavior and reassures us, “Kudus do not lie. Impalas will alarm call to fake out other males and take over a herd of females, but kudus are trustworthy.”

We head south out of camp, taking a path lined with grasses most palatable by the animal we are looking for, occasionally pausing to gather additional clues: another alarm call, the scattering of frightened herbivores, tracks from a predator. While we don’t find any evidence of kudu or kill, no one feels cheated. We’ve learned along the way.

“That’s the best part of my job,” Julien says. “Watching people piece together signs, use their instincts and problem solve. I take a lot of pride in watching each person develop their skills out here.”

Naturally more animated than Jami (or pretty much anyone), Julien’s excitement infectious. If I had to create an emoji for him, it would simply be this: !!!!!!!!!!!!!!. He lives in a world of exclamation points and could find overwhelming joy in a bowl of oatmeal.

“You guys are good luck! I’m going to shrink you all down and put you in my key chain so you can always be on safari with me,” he tells us one night aft er seeing his first African wild cat.

“You guys are good luck! I’m going to shrink you all down and put you in my key chain so you can always be on safari with me,” he tells us one night aft er seeing his first African wild cat.

He is so thrilled by the find he starts to tremble. So much so we begin to wonder if he’s having a seizure. Once we are satisfied his reaction is not related to a medical condition, we quickly catch his enthusiasm—and what moments prior seemed no more remarkable than spotting a stray house cat has now become our favorite game drive sighting ever.

“People remember emotions and actions. I could have pointed out the African wild cat and kept my response in check, but then the experience is only my own. Happiness should be shared, not contained,” he explains.

It’s a subtle message for those students hoping to become guides—excitement is a rapid breeder.

And while it might be part of the intangible curriculum, Julien’s seemingly over-the-top responses are as genuine as they are frequent. It’s not uncommon to hear him exclaim, “Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god! Look at this lovely, lovely, bee!”

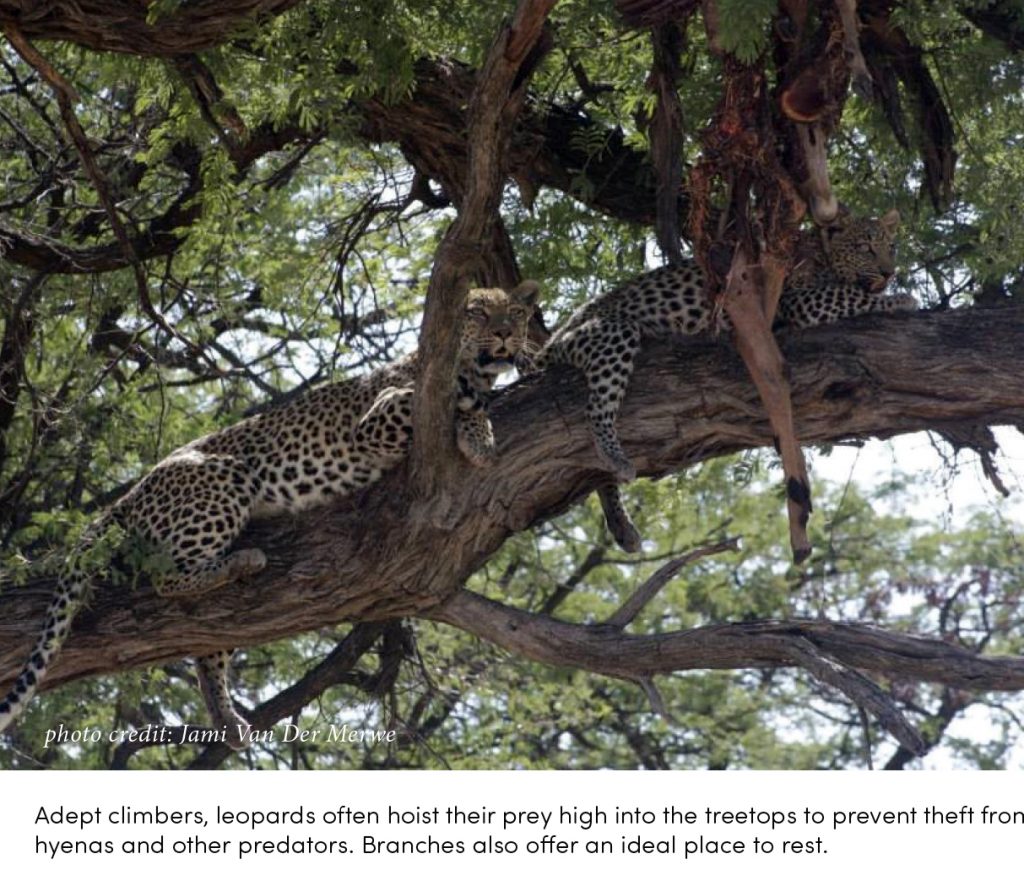

He really is just as stoked about bees as he is leopards.

“I think I was born that way,” he acknowledges. “You’ll be hard pressed to find a photo of me as a child without a snake or a bug or something squirming in my hands. I have always been fascinated by every living organism and its connection to our ecosystem.”

“I think I was born that way,” he acknowledges. “You’ll be hard pressed to find a photo of me as a child without a snake or a bug or something squirming in my hands. I have always been fascinated by every living organism and its connection to our ecosystem.”

That fascination is the invisible thread that connects Grant, Jami, and Julien to this life of simplicity and appreciation. It is intentionally sought, woven with purpose, not required by circumstance. They are not bushmen by social or economic default. They have lived in cities, studied at universities and are fluent in multiple languages. With occasional exception, they don’t communicate in grunts. Their animal-like behavior is limited to the intermittent display of male dominance and a frequent laugh that strongly resembles the call of a silvery cheeked hornbill. Th ey have smart phones, social media accounts, and appreciate a cold beer.

This is what makes the Okavango Guiding School’s Kwapa Camp special. The people there have chosen a simple existence because they cherish nature for its constant wonderment and teaching. Th eir ethical commitment to the bush is what separates them from those who just happen to occupy the role of safari guide. Th ere is no eff ort at life plagiarism; it is who they are.

To say Kwapa Camp is not a soft adventure is perhaps the biggest understatement since the captain of the Hindenburg said, “I smell gas.” You will be filthy, you will be smelly, you will be exhausted. But you will also be changed. Those who visit this place leave as better humans; reconnected to their purpose, with a firm grasp on the invisible thread that connects us all.

To learn more about the Okavango Guiding School and the courses offered, visit: guidetrainingcourses.com.

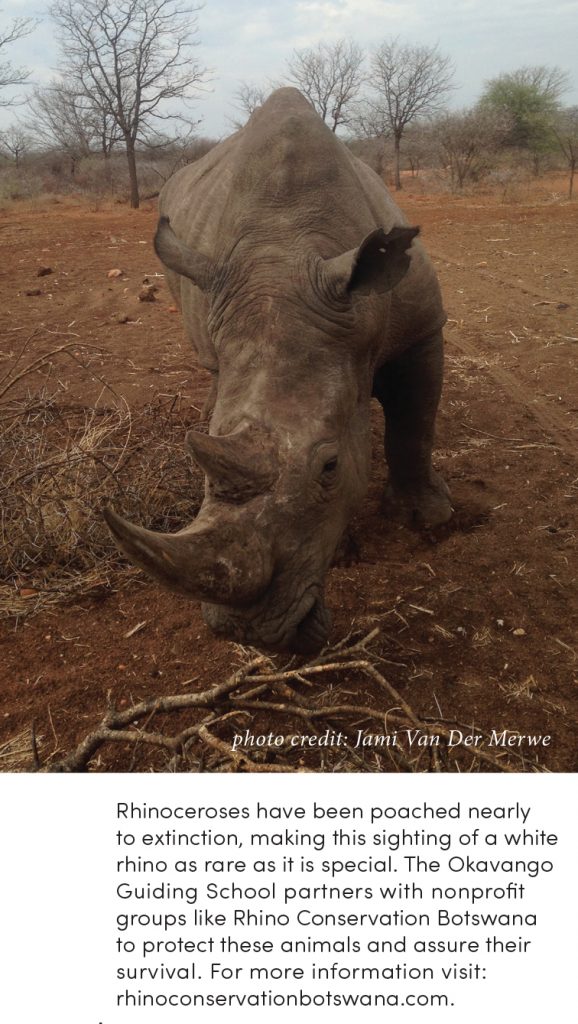

By Amy Roberts